Big Data Plays Arresting Role in White Collar Crime

User-friendly analytics tools with graphical presentation tools plus big data solutions and the ability to more easily search and track fiscal anomalies give financial crime fighters a much stronger arsenal in their ongoing battle against white collar crime.

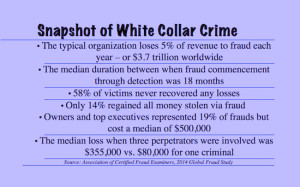

These offenses costs taxpayers up to $600 billion annually, but the complexities of these cases mean many financial scammers elude justice for years, if not forever. That could – and should – be changing, however, as investigators leverage powerful databases, big data, and analytics to find and expose schemes, then use this information to empower juries to follow the money trail.

The opposite, however, appears to be true. At a time when agencies have the ability to better equip themselves, federal prosecutions of these criminals is at its lowest level in two decades, according to a July 2015 report by Syracuse University. This year, the federal government is on track to prosecute approximately 6,897 individuals for white-collar crimes, the university's Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) determined. This figure is 12.3 percent less than last year and 29.1 percent less than in 2010, TRAC said.

Prosecutions declined for multiple reasons. The Justice Department increasingly used special agreements that allow corporations and their executives to avoid being prosecuted: In 2003, these deals were virtually unused, according to a report by George Mason University's School of Law. Between 2007 through 2011, prosecutors resolved 44 percent of cases via deferred prosecution or non-prosecution agreements. Despite calls to "hold Wall Street accountable," the financial industry's lobbying efforts and donations created a "too big to jail" environment in President Barack Obama's government, International Business Times wrote. Top White House officials argued prosecuting large enterprises for financial crimes could result in bankruptcies, mass layoffs, and stock market upheaval, wrote IBT.

Finally, the Justice Department's headcount shrunk 15 percent and its budget for travel, consultants, and overtime, all vital for investigations, were cut, IBT reported, citing the department's budget statements.

These cases also are difficult to translate into layman's terms, Pete Platt, a retired Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Special Agent and former financial investigator with the Department of Justice (DOJ) – where he also worked at the Drug Enforcement Agency – who is now fraud investigations manager at a bank. "If the case is too hard to explain to a jury, prosecutors will just walk away from it," he told EnterpriseTech.

But do these arguments mean white-collar criminals should start thinking bigger? Or could today's technologies help compensate for smaller staff sizes and simplify the process for federal agencies?

White Crimes, Dark Hearts

Financial criminals range from corporations engaged in organized wrongdoing to street gangs, from pyramid schemes and insurance fraud, to securities and commodities fraud to money laundering and healthcare fraud, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Dollar amounts vary from several hundred dollars to millions collected over years from hundreds of victims across multiple jurisdictions.

One thing seldom differs: These white-collar criminals attempt to hide their wrongdoing via complicated financial maneuvering, multiple bank accounts, and other schemes that are difficult to track, said Pete Platt, a retired Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Special Agent and former financial investigator with the Department of Justice (DOJ) – where he also worked at the Drug Enforcement Agency – who is now fraud investigations manager at a bank.

One thing seldom differs: These white-collar criminals attempt to hide their wrongdoing via complicated financial maneuvering, multiple bank accounts, and other schemes that are difficult to track, said Pete Platt, a retired Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Special Agent and former financial investigator with the Department of Justice (DOJ) – where he also worked at the Drug Enforcement Agency – who is now fraud investigations manager at a bank.

"The crooks, for the most part, are almost always one step ahead of the people chasing them. It's always been my effort to think a couple of steps ahead of the game to try and catch them," Platt said.

This form of crime is often under-reported, in part because victims may not know they have been robbed or feel ashamed they fell prey to scams. In other cases, these crimes get less publicity since some believe victims are partly to blame for their bad judgment, said Susan Deehan, chairwoman of Actionable Intelligence Technologies (AIT), in a statement.

Armed for Success

In the past, agents used huge spreadsheets to track accounts, assets, payments, and other financial information, said Platt.

"I used to use accounting column paper, then computers came around and we moved to Excel spreadsheets. No matter how we did it, when it came to trial we had to redo it in another program," he said, recalling the process of trying to make complex financial data palatable to juries.

Today, though, he uses AIT Comprehensive Financial Investigative Solution (CFIS), which automatically processes paper and electronic documents, and records them in a centralized database. It then performs data analysis, graphic visualizations of financial transactional patterns, flow of funds tracing and analysis, and reporting.

"You can see patterns, you can see trends that are sometimes very revealing," Platt said. "From a jury standpoint, it is dynamite. When you show a jury some of the analytics AIT produces, the result is, 'Whoa. It can be nothing else but money laundering.'"

Financial fraud can generate hundreds of thousands of records, said Tim Deehan, president of ATI, in an interview. An FBI agent determined one DEA case would have taken 123 years to input the data, an obviously impossible task to accomplish via spreadsheet and human clerks that took several weeks in ATI, he said. In another example, a prosecutor inherited a medical fraud case after her predecessor planned to dismiss it because of the complexity; she used ATI to process the data and got a 45-count indictment, Deehan added.

"The doctor had learned exactly how to do the fraud so that they couldn't, not necessarily detect him, but if they did detect him they couldn't devote the manpower to prosecute him," he said.

The ability to thoroughly follow every income source and determine whether it is legitimate or questionable, figure out whether individuals suddenly have too much income for their job, or follow an organization's convoluted defensive mechanisms to prove financial fraud may prevent some potential white-crime wannabes from entering the fray. It puts money back in the pockets of taxpayers and victims, and metes out justice to those who committed crimes, often over several years to many people.

"If you're going to investigate a group, you want to investigate every illicit source of money and get it back for restitution back to victims or law enforcement to fund more investigations," Deehan said. "That's the only way you're going to permanently disperse an organization. If you leave the organization because you can't find all the records, you'll have some of the operation still operating."

Related

Managing editor of Enterprise Technology. I've been covering tech and business for many years, for publications such as InformationWeek, Baseline Magazine, and Florida Today. A native Brit and longtime Yankees fan, I live with my husband, daughter, and two cats on the Space Coast in Florida.