The New Fabrics and Mix-and-Match Systems: The Next Big Thing in Data Center Servers?

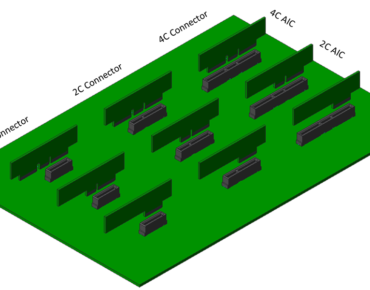

Gen-Z edge connector

If you’ve wondered about the new fabric efforts undertaken by the Gen-Z, OpenCAPI and CCIX consortia – if you’ve wondered what it all means – here's a way to look at the problem they're taking on: it's akin to pre- and post-EU Europe. Before the EU, financial transactions that crossed national borders came with a currency fees, impeding trade; after the EU, a common currency enabled money movement without added cost, promoting commerce. In the same way, data center server computing today is a multi-protocol Tower of Babel, a myriad of data communications formats within the processor and among systems components requiring "translation" overhead that drains compute resources (and boosts energy consumption) from the analytics workload at hand.

That’s what the three fabric consortia have set out to address, and if they achieve their visions, advanced scale servers in cloud and on-prem data centers could be on the cusp of major change.

To gain better understanding of the emerging fabrics we turned to Bob Sorensen, VP of research and technology at analyst firm Hyperion Research. Before speaking with him, we had already grasped that the fabric projects were onto to something important, that they have impressive membership rosters stocked with industry leaders (though not Intel, more on that below), and that they could take strides toward achieving the vaunted goal of data-centric, or memory-centric, computing, in which processing is bumped from the top spot of the computing hierarchy and placed more at a peer level with other system functions, where a range of general purpose and accelerated architectures can be used simultaneously, according to workload need, while larger masses of data are flashed around the system placing more information in live memory.

To gain better understanding of the emerging fabrics we turned to Bob Sorensen, VP of research and technology at analyst firm Hyperion Research. Before speaking with him, we had already grasped that the fabric projects were onto to something important, that they have impressive membership rosters stocked with industry leaders (though not Intel, more on that below), and that they could take strides toward achieving the vaunted goal of data-centric, or memory-centric, computing, in which processing is bumped from the top spot of the computing hierarchy and placed more at a peer level with other system functions, where a range of general purpose and accelerated architectures can be used simultaneously, according to workload need, while larger masses of data are flashed around the system placing more information in live memory.

We turned to Sorensen’s talent as a technology translator because articles we’ve seen about the new fabrics usually dive headlong into the technical tall weeds, overgrown with talk of “memory semantic access to data and devices via direct-attached, switched or fabric topologies” and “high-speed processor expansion bus standard.” If that’s your cup of technology content tea, cool. But if you’re interested in more of a primer, read on.

According to Sorensen, the new fabrics are an attempt to overcome current barriers to baseline communication needs within systems.

“There are so many different components,” Sorensen said, “of processors, GPUs, of other types of accelerators, like FPGAs, and then a plethora of memory capabilities, like PDR4, NVRAM, burst buffers that are specialized kinds of memory, then you’ve got solid state disk (storage) and traditional file system.

“The ability to connect all those things in an efficient way is relatively complicated. For example, you’ve got NVMe, which is kind of PCI Express for non-volatile memory, so that’s different from if you’re talking to DRAM memory, and different if you’re talking to solid state disk. So there’s all these protocols that are clogging up the system right now because you’re talking to different kinds of devices and treating them differently… The communications overhead is considerable because the protocols all evolved differently, it mucks up the system. It’s like an exercise in communications at the U.N.”

“The ability to connect all those things in an efficient way is relatively complicated. For example, you’ve got NVMe, which is kind of PCI Express for non-volatile memory, so that’s different from if you’re talking to DRAM memory, and different if you’re talking to solid state disk. So there’s all these protocols that are clogging up the system right now because you’re talking to different kinds of devices and treating them differently… The communications overhead is considerable because the protocols all evolved differently, it mucks up the system. It’s like an exercise in communications at the U.N.”

So the fabric consortia are developing on a common language that enable users to plug in the CPU of choice, the GPU of choice, the memory system of choice, a common language that allows vendors and systems suppliers to build systems without spending time, effort and money on “translation” software overhead.

“By the same token,” Sorensen added, “the component vendors can ultimately broaden their market because they don’t have to be locked into one particular series of vendors, or a particular series of standards, or (worry about) the cost of supporting a number of standards. They’d love to see all this become very, very simple.”

Along with new server platforms from the likes of Dell EMC (a Gen-Z member), the intended flexibility of the new fabrics is a major potential attraction.

“The whole mix-and-match issue becomes that much more simple,” Sorensen said, “and in theory it offers significant performance capabilities because now you don’t have to have a bunch of translators standing around the Tower of Babel, because everyone kind of speaks the same language, the translation overhead goes away. So it offers a generality in architectures, but it also offers a significant performance improvement because you just don’t have to deal with the overhead of managing the various languages that each device requires today.”

![]() For moving data within the system, adoption of high speed communications links, such as NVLink, developed by OpenCAPI member Nvidia (and also adopted within the Gen-Z standard) and offering greater bandwidth than PCIe, is a critically important feature for achieving data, or memory, centrism in support of data-intensive HPDA (high performance data analytics) and machine learning.

For moving data within the system, adoption of high speed communications links, such as NVLink, developed by OpenCAPI member Nvidia (and also adopted within the Gen-Z standard) and offering greater bandwidth than PCIe, is a critically important feature for achieving data, or memory, centrism in support of data-intensive HPDA (high performance data analytics) and machine learning.

Sorensen cited a recent visit to Oak Ridge National Labs and a discussion he had with managers of the Titan supercomputer, hamstrung by an interconnect bus not suited for the data-intensive demands of the system.

“For the earlier Titan system their interconnect scheme was basically PCI Express, which they referred to as ‘the straw,’ transferring data back and forth through a straw,” he said, “whereas now the GPUs and CPUs are talking to each other through NVLink… They can take that to its logical extension with some of these things. I think what it offers is the ability for people to look at their memory and processing requirements and put together a system that meets their needs in a more customized mode, and also with better performance.”

He also cited ORNL’s IBM-OpenPOWER-Nvidia-based Summit system, the no. 1 ranked supercomputer in the world, according to the latest Top500 listing, as a harbinger of things to come.

“The fact that there’s so many options now for interesting kinds of memory – if you look at a Summit node, it has GDR4 DRAM, it’s got high bandwidth memory and it’s got persistent memory, so each node has three different types of memory. That, in the old days, all would have been DRAM. But now because of performance characteristics, cost concerns and systems architecture, you can use different kinds of memory nowadays to meet different computational requirements.”

Notable by its absence from the memberships from all three consortia is Intel, whose Scalable Systems Framework and Omni-Path high performance communication architecture are efforts by the chip giant deliver on many of the same objectives. But a driving ethic of the consortia is the embrace of more systems component flexibility outside of the Intel infrastructure.

“If you look behind the scenes at all this,” said Sorensen, “a lot of these are efforts to break a little bit out of the Intel dominance, with Intel defining the interconnects. Because if you buy Intel components, they come with things like Intel Quickpath, which is what connects the processors and accelerators. They’re looking at Omni-Path, which is perhaps more network-centric, for connectivity. These alternate suppliers – IBM and AMD, and Mellanox, and even some of the data center suppliers – they’re looking for more choices, more options, to kind of offer products outside the Intel domain. I think that’s driving some of this standardization issues as well.”

In some respects, Sorensen said, Intel isn’t only in conflict with other server and components suppliers, the company is also dealing with “the procurement power of the cloud services companies (FANG) and hyperscalers.

“They want to have the option to build the kind of servers they see serving their customers, and (they want to break out of) the idea of locking into a single vendor… Intel’s made it pretty clear they’d like to be viewed as a data center supplier, not just as a chip supplier. That, I think, creates a certain amount of angst with the large user base of the data center folks, who’d much rather have the ability to mix and match at every level, for price and performance reasons.”

Sorensen declined to pick a winner among the three consortia, stating it’s too early to know. He did, however, note that there is potential for the consortia to duplicate efforts and to come into conflict.

“They’re all relatively new, and they have somewhat different technical specifications and different ideas of where they want to go,” he said. “Each have various traits and weaknesses. What I hope is there’s an emerging confluence of interests between them…, as opposed to these three organizations stove-piping themselves, because the last thing we want to see is more fragmentation here.”

He did venture, in general terms, that “perhaps the winner is the most inclusive, and the one that tries to steal a march and take ownership of all of this is the one I think is going to be frowned upon the most.”