Groundwater Flows through New Datacenters

Supercomputers harbor a double whammy of high energy usage. First, the applications and simulations they run are intense, with trillions of calculations that use up a lot of energy. Second, that energy usage translates to heat generation, which needs be sifted out of the system for the machines to run smoothly.

Supercomputing operators have to be more environmentally conscious than average to account for growing carbon and energy costs. So how does one reconcile that general aspiration to reduce costs and carbon emissions with the often environmentally-unfriendly nature of supercomputers and large datacenters?

Supercomputing operators have to be more environmentally conscious than average to account for growing carbon and energy costs. So how does one reconcile that general aspiration to reduce costs and carbon emissions with the often environmentally-unfriendly nature of supercomputers and large datacenters?

One solution may be to use the Earth to provide the facility’s power and cooling. To be more specific, instead of drilling into the Earth to harvest minerals or oil to fuel electric power plants, whose energy gets directed to the computing centers, one could use the Earth’s natural groundwater to either power or cool facilities.

Two facilities in particular, one in Iceland and another in Western Australia, are using groundwater to either power or cool their respective facilities. In the case of Iceland, the groundwater is heated as a result of convection from the underlying magma. This water is heated by the Earth to the point where it naturally forms a steam, which can then turn a turbine and generate power. This is known as geothermal energy, and its use would go a long way to decreasing a facility’s carbon footprint.

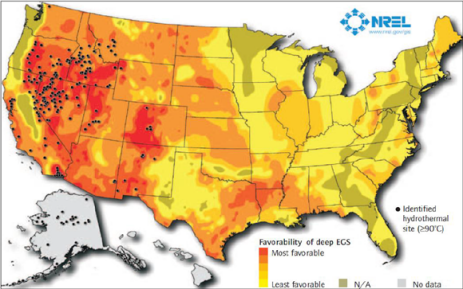

There are, however, quite a few limitations regarding geothermal energy to power an intensive computing environment. The first and perhaps most important is the location aspect. Not every region’s groundwater is sufficiently heated to create steam, spin turbines, and produce power. In general, prime areas for geothermal energy are around fault lines and mountain ridges. The figure below represents where these hotspots lie in the United States.

As one can see, the geothermal energy sites straddle the Rocky Mountains and the California fault line. As such, the scale of geothermal energy is limited in the sense that few people want to build extensive datacenters in these environmentally hazardous locations.

However, this principle of location-driven data centers is nothing new, as many facilities are built with an eye toward open-air cooling. The MGHPCC utilizes this, as does the Facebook center located in Oregon.

Iceland being relatively cool year-round and lying atop active volcano sites, indicating strong geothermal potential, is in a prime position to run a very clean datacenter. "Iceland is the only place on earth with 100% renewable energy from dual sources, geothermal and hydroelectric," said Jeff Monroe, CEO of Verne Global, the company whose datacenter is run entirely on natural renewable energy.

Iceland’s climate allows the machines to cool naturally for the most part; eschewing expensive cooling mechanisms that themselves can run up the wattage of a facility. Changing the temperature of water requires more energy after all than changing the temperature of any other material.

While a Google-like server will use up to 200 megawatts, the Verne Global Iceland datacenter can run 400,000 servers using half the wattage.

Not everyone can rely on climate to cool their systems, however. Some supercomputers out there are trying to analyze genetic patterns to find the true cause of disease. Others are trying to model the universe. The amount of calculation and computing required to approach those lofty goals is immense. And all of it needs to be powered. Those machines cannot run hot.

In nature, when proteins are exposed to excessive amounts of heat, they denature, or fall apart. Mistakes are made as those proteins were specifically designed by the DNA to perform a task. Computers similarly ‘denature’ in high temperatures. Temperature is defined as an average kinetic energy of molecules. In layman’s terms, this means that higher temperatures result in more excited particles. These more excited particles have a tendency to jump and wreck the careful balance of electric and magnetic fields inside a supercomputer.

To put it simply, cooling is of immense importance. It is also usually expensive. However, the Pawsey Centre, which is building a Cray supercomputer, plans to use groundwater to cool their facility.

"The system is known as groundwater cooling, and works by pumping cool water from a depth of around 100 metres through an above-ground heat exchanger to cool the supercomputer, then reinjecting the water underground again," said CSIRO’s (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization) project director, Steve Harvey.

This development has been made possible by recent supercomputing advances that allow the machines to run at higher temperatures. While some facilities are still uncomfortable with computing at above 20 degrees Celsius, there exists a great opportunity in terms of energy saving for newer data centers and supercomputers such as the one being built in Western Australia.

“Recent global changes in the cooling requirements for supercomputers, however, means that we can now use water of an ambient temperature, as opposed to chilled water,” explained Harvey about why natural water can be used in favor of child water. “That's where groundwater cooling comes in."

Most supercomputers in Australia utilize cooling towers, which essentially act as silos for water cooling. Needless to say, that process is expensive and energy-intensive along with being somewhat wasteful of water. CSIRO figures they will save 38.5 million liters of water through their groundwater cooling, since all of the water will be returned to its source after usage.

The Earth provides many ways to power and cool the computing centers of the world that do not involve oil or the burning of carbon-heavy minerals. In order for advancements like the exascale computer to be considered worthwhile, these technologies may have to be implemented with higher frequency. Iceland’s and Western Australia’s facilities represent positive steps in that direction.

Related Articles

Massachusetts Universities Plant Green Datacenter

Obama's Address Outlines Green Strategy