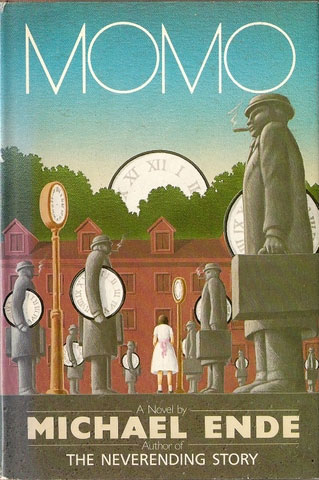

Time is Momo

In the United States, German novelist Michael Ende is best known for his towering masterpiece The Neverending Story, but really, his body of work is composed entirely of towering masterpieces. Among the handful translated into English is a slim novel called Momo.

Momo is an orphan who lives in the ruins of an old amphitheatre on the outskirts of a town. No one knows where she came from, but grown-ups and children alike love her, because she’s such a good listener. People can just pour out their troubles and cares while she listens, and suddenly they know what to do. The games kids play are always more fun when Momo’s around, too; their imaginations are fired up and they turn the amphitheatre into a world of adventure. The townspeople bring her food and take care of her, and life goes on in a rustic, pleasant, unrushed sort of way.

Momo is an orphan who lives in the ruins of an old amphitheatre on the outskirts of a town. No one knows where she came from, but grown-ups and children alike love her, because she’s such a good listener. People can just pour out their troubles and cares while she listens, and suddenly they know what to do. The games kids play are always more fun when Momo’s around, too; their imaginations are fired up and they turn the amphitheatre into a world of adventure. The townspeople bring her food and take care of her, and life goes on in a rustic, pleasant, unrushed sort of way.

Then one day men in grey suits arrive, representatives of the Timesaving Bank. People in town waste too much time, they claim – instead, citizens should start saving it by cutting out leisure activities and pointless daydreaming.

Soon the entire city is under the spell of the Time Thieves, and the more time people “save,” the less they seem to have. They make more money, maybe, but they don’t visit friends, or enjoy a sunset, or play with their children. They take no pride in their work, doing only what is necessary to get finished and move to the next task. They’re harried and miserable, and no one goes to see Momo anymore.

The Time Thieves can’t touch her, since she has plenty of time and no interest in saving it. As such she’s the only person who can free the city before everyone simply saves themselves into nonexistence.

Clearly there are good and bad ways of saving time.

Blindly cutting out everything that brings us comfort in an ill-conceived rush to accomplish more, that’s the bad way.

Thoughtfully applying new tools and new solutions to make the world a better place, that’s a good one.

This reality was brought into stark focus for me during a recent project with NCMS, during which one of our member organizations sat me down and spelled out in plain English what precisely it meant to apply HPC to their manufacturing challenges.

It meant they saved time.

But to leave it at that is a disservice. The company – L&L Products in Romeo, Michigan – didn’t just do its work faster. It did work it could not have otherwise done, period, because without modeling and simulation, there would have literally not been enough time to do it.

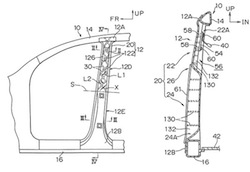

For example, L&L’s Composite Body Solutions product line innovates a variety of materials that can act as inserts, adhesives, or supports for metal parts in automotive or aerospace applications. The pillars protecting a car’s passenger compartment may be largely made of high-strength steel, but one of L&L’s glass-infused nylon inserts could make it an order of magnitude more resistant to buckling.

As with anything, you need to take engineering realities and business realities into account when creating a product. Sure, it’d be “safest” to engineer vehicle pillars out of solid titanium. They’d be a nightmare to manufacture, weigh a ton and a half, and cost $300,000, but hey. Car’s safe, right?

As with anything, you need to take engineering realities and business realities into account when creating a product. Sure, it’d be “safest” to engineer vehicle pillars out of solid titanium. They’d be a nightmare to manufacture, weigh a ton and a half, and cost $300,000, but hey. Car’s safe, right?

But reality demands that a low-cost, light, easy to work with solution that exceeds safety requirements – but doesn’t turn the car into a tank – would be preferable.

Enter L&L.

L&L could take a number of potential approaches when creating a pillar insert that meets the specifications provided by the OEM client. There’s the rub: “meets specifications.” That phrase doesn’t mean optimal; it means acceptable. It does its job. And while we don’t want to get too down on something that does exactly what it’s supposed to, there’s a bit of Momo’s time-savers there; people only doing what needs to be done rather than take the time to do something truly special.

Because creating an optimal solution takes time. Obviously. The more time you have to work on something, the better it’s likely to be.

And that’s what L&L got through application of modeling and simulation: the tools did the work so much faster that they suddenly had the breathing room to optimize, not just meet spec. Predictably, the more time these tools could save, the more optimal the products become.

A challenge that I face in helping drive the adoption of digital manufacturing is finding a good, clear, concise way to explain exactly what it will do to empower those who adopt it. Now, “It’ll save you time” is probably not strong enough on its own, just as randomly or carelessly saving time doesn’t bring any satisfaction or benefit. But if I could point to companies like L&L, though, and say flat-out “they did something they couldn’t have done without it, something that literally doubled their bottom line, all because they adopted tools that allowed them to do six months of work in six weeks,” well, that might be a little more compelling.

A challenge that I face in helping drive the adoption of digital manufacturing is finding a good, clear, concise way to explain exactly what it will do to empower those who adopt it. Now, “It’ll save you time” is probably not strong enough on its own, just as randomly or carelessly saving time doesn’t bring any satisfaction or benefit. But if I could point to companies like L&L, though, and say flat-out “they did something they couldn’t have done without it, something that literally doubled their bottom line, all because they adopted tools that allowed them to do six months of work in six weeks,” well, that might be a little more compelling.

Time is, after all, money.